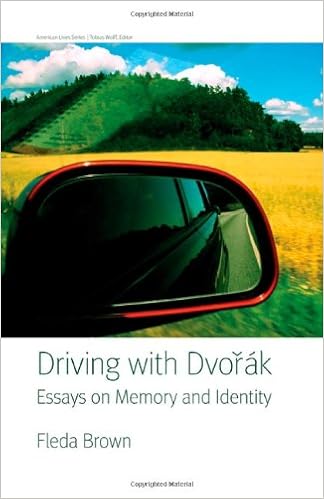

Fleda

Brown’s memoir, Driving with Dvorak, selected by Tobias

Wolff, for the American Lives Series from University of Nebraska,

invokes the elegiac tradition while Brown drives us across spaces as

wide as America itself: the architecture of family, marriage, divorce

and re-marriage, and the essential defining of self. And Brown pulls

us into her history, her ruminations on identity, “Who am I? How do

I begin?” And where Brown goes her reflective eye and poetic voice

follow.

She

is at home in her skin, her body, but cuts memories to the bone as if

she were a butcher, separating the lean from the fat. In the title

essay, Brown’s father, “someone to love and fear” appears to

her as a greaser, and then as memories of hot summers where his edge

boiled over into rage. At times you feel she wants to let him off the

hook, as if she understands that he was trying to keep the family

together, her sisters, their needs, and the exhaustive needs of her

brother, Mark, disabled and inert. There is weight and pain in her

memories, wondering what it would be like if her father and brother

were to drown when Mark goes overboard one summer day, “I don’t

know what I want to happen, what I feel, what solution would make the

world a better place for us.” These truths turn up like polished

bones in the long tidal rhythms of her prose. I suppose that’s

what’s cool about the music of elegy, it’s haunting, aching, and

pretty, and touches a key of doom that humans feel when they love too

much.

In

“Hiking with Amy,” her stepdaughter, Brown questions identity,

family, relationships, her chorus, if you will, but in “Hiking”

she also questions her age, her ability to maintain pace with her

stepdaughter. She goes to the gym, but what does that really mean,

anyway? Maintenance? A kind of totem against becoming one’s

parents? And indeed Brown is “pitting myself against

so I won’t have her dowager’s hump, walking and running, watching

my eating so I won’t have her stomach. Everyday I wake figuring how

to live.” And throughout the hike and essay her sense of self is

mercurial, she is ten, she is ancient, she has no gender, no

definitions but the act of hiking and the very fact of the wilderness

about her. Her identity wavers and gives, and enlarges with

experience.

Brown’s

sense of identity and how our whole lives are built around

reconnecting with who we are, and who we want to become is compared

to buying a new car, in the essay “New Car,” where vehicles, like

marriages, become the sum of many dings and defects. Like the many

cars we have had a relationship with, there are memories and

touchstones to each vehicle. In “Car” Brown interrupts her

narrative with mini factual narratives about the makes and models she

has had a relationship with over the years, and the result is an

emotional undercut to Brown’s history and memory. A brief reminder

that the world is a place that is made and sold and bought, and that

we simply maintain.

Throughout

these essays, the poet’s voice is consistent; her eye is

consistent, even though the speaker aches to be redefined. Consider

“Showgirls” an essay about her ill sister, about Vegas, about

poetry, and always about one’s search of self-identity, a search

that Brown understands is a loop, and is endless and always. Brown’s

search is our search too, and when she returns to memories of her

father she does so tentatively; the ache in such hesitation ripples

throughout her prose. “Where does one go to find life? There is

only the vertical, only the awareness of each moment, even as it

gathers its own version of past and future to itself.” There is

only the moment, and how we adapt to its additions and subtractions,

a reflection in the rear view mirror that changes like the landscape

we pass through.

Comments